Printable Version

VOL 2, NO 2

April 1999

FAITH AND PLACE: Religion and the Metropolis in Historical Perspective

by Etan Diamond

�Present-day Protestantism is challenged by the urban situation in much the same way that the primitive church was challenged by paganism.�� So began Walter Smith, Jr., in his 1958 report to the Indiana Conference of the Evangelical United Brethren.� Just as winning the pagan was �an almost insuperable responsibility,� so too �urban conditions, which include mobility, anonymity, transiency, vicious competition, conflicting social groups, and constant change, confront the church with such gigantic difficulties that many times the church is tempted to believe that the job cannot be done.�� Moreover, the traditional ways of thinking about the city � urban, suburban, rural � were rapidly losing their relevance in the postwar period.� �The city, with its problems, is engulfing the suburbs.� Urbia and suburbia are losing their separate identity as urbanization continues.� Consequently, no church is separate from the problems confronting the city church.� The church must be awake to seize every opportunity to meet human need in its changing environment.�

Smith was not alone in his assessment of the changing city.� In the postwar period, almost everyone involved in religious life, from denominational officials to congregational pastors to lay leaders, recognized that the changing metropolitan landscape was dramatically restructuring the religious landscape.� Study after study found, as church consultant Frederick Shippey wrote in 1946, that �all religious work goes on in this [urban] context.� Once a church has rooted itself into the life of the community, it must remain alert to the alterations which come within the urban environment.� Change is surely inevitable.�� From the 1940s forward, American cities expanded dramatically.�� New suburban development pushed the urbanized area out toward the periphery, reshaping both the rural landscape and the urban landscape left behind.� New and different people, new and different industries, moved to and within cities.� Political alignments shifted with the shift to suburbia.�

These changes over the past half century challenged people�s understanding of place and space in the city. Concepts such as �neighborhood� and �city,� and perhaps most of all, �community,� were ripped apart and put back together in sometimes very different ways.� Metropolitan expansion led to increased mobility, which created new environments, neighbors, and institutions � all of which meant new communities.� For many people, this changing sense of community was felt most clearly in the religious environment.

As an institution structured around community and rooted to particular places of worship, religion could not help but be shaped by the constant swirl of physical and social mobility that dominated the metropolis.� In inner city neighborhoods, white flight and black in-migration challenged the status quo of many congregations.� Some white congregations saw their membership move completely out of the neighborhood, often to another church, leaving a handful of members to face a much different neighborhood, socially and economically.� Some congregations chose to relocate to the newer areas, while others decided to reorient their church mission to the new environment.� On the rural fringe, where small church buildings had sufficed for a small community, such facilities suddenly proved inadequate to accommodate the influx of suburbanites.� In many new suburban areas, new churches were organized, and functioned as gathering and meeting places for entire neighborhoods of newcomers.� In all of these situations, individuals experienced a changing sense of community.� For some, the church served as a place to plant new roots; for others, it offered a chance to hold on to what roots they could.� In short, religion served as an important mediating institution amidst rapid changes in the metropolis.�

Recently, Hartford Seminary professor Clifford Green has called for understanding the metropolis and its religion as an �interconnected whole.� This comment echoes the earlier comments of Shippey, Smith, and others in the 1940s and 1950s.� It also parallels observations of urban scholars who argue that the metropolis is a single ecological system that cannot be understood piecemeal.� A single episode � the suburban relocation of a religious congregation, for example �� comprises the stories of three groups: those who moved to the suburb; those who remained in the urban core; and those who were already living on the rural periphery.�

Only a handful of scholars have undertaken to explore what historian Diane Winston has described as �the ways individual and corporate religious behaviors affect urban life and vice versa.�� When historians do talk about religion, they usually do so in the context of ethnicity.� They write about Polish Catholics, Russian Jews, German Lutherans.� Similarly, religious studies scholars have focused more on national denominational stories or on narrowly focused local congregational histories than on the mid-level analysis of religion in metropolitan regions.

Academic scholars and religious practitioners alike should care about the historical evolution of the city because understanding this evolution can help explain the changes that are happening to the people in the pews.� Consider this small but telling example about metropolitan space.�

Until the middle of this century, people�s conceptions of proximity and distance were closely correlated.� Things physically nearby were perceived as �close,� while physically distant places were �far.�� But changes in transportation and communication technology changed this dynamic.� As historian Robert Fishman has argued, the metropolis is now structured around time, rather than distance.� Because people can travel great distances quickly, they may perceive things as close even when they are not nearby.� For congregations, this represents a dramatic shift.� What does it mean to have a congregation that is geographically scattered yet still feels some tie to a church?� What does �neighborhood ministry� mean when metropolitan growth has transformed the neighborhood into something much larger?� How can you define �community� when you can�t physically see it?If we apply this model to Indianapolis over the past half century, it becomes clear that the stories of religion and metropolitan development are closely linked.� The following are four examples of this linkage:

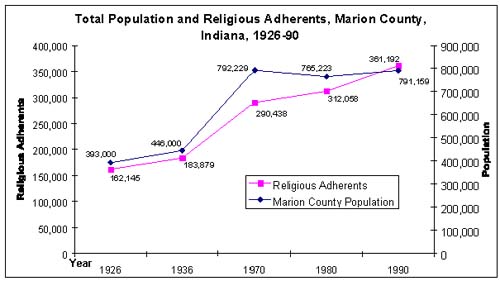

1.� Religious Adherents.� As a whole, religion as measured by the number of adherents has kept pace with the city�s population growth since the 1920s.� Data from federal censuses of religion in 1926 and 1936 and national surveys on religious adherents by the Glenmary Research Center in 1970, 1980, and 1990, reveal that Marion County�s religious adherent totals roughly parallel the rise in population.� Only in the 1980s does the number of religious adherents seem to rise faster than the population, raising the question of whether Indianapolis is in the midst of some sort of religious expansion. �What has happened since 1990, and what direction this trend is going, are two important points to watch over the next few years, when data from the 2000 census of population and new Glenmary data on religion will be released.

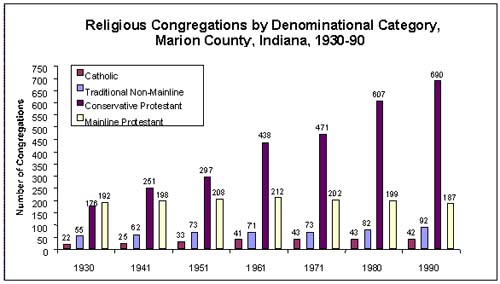

2.� Congregational Distribution.� Despite the general parallel between Indianapolis�s religious landscape and its population, there has been considerable variation within this religious landscape.� Specifically, the growth in the number of conservative Protestant congregations stands out from the stability of the mainline Protestant churches or even the modest increase in Catholic and traditional non-mainline congregations.� Given the extent to which conservative Protestant congregations dominate Indianapolis�s religious culture, one might conclude that these groups also dominate the city�s secular civic landscapes.� Yet, as other qualitative evidence shows, these conservative Protestant groups have made few inroads into the city�s civic, political, and economic culture.� Throughout the century, Indianapolis�s major civic organizations have been led by individuals from mainline Protestant backgrounds, with the conservative Protestant community largely absent from leadership circles.� It remains to be seen whether this historical imbalance will right itself, with conservative Protestants moving into positions of civic power.3.� Religious Geography.� The question of whether conservative Protestantism will gain civic power is connected to Indianapolis�s religious and social geography.� Indianapolis has historically been split by a stark north-south cultural division, with the north side viewed as wealthy and moderate (and in control of civic power) and the south side as working-class and conservative (and outside the corridors of political and economic power.)� Religiously, this split translated into mainline Protestantism on the north side being counterpoised against south side conservative Protestantism.� Since the 1950s, however, both the secular and religious realities have changed.�� Parts of the south side rank among the city�s higher socioeconomic areas, while pockets of poverty dot the north side.� The north side can no longer be thought of as a bastion of liberal Protestantism.� From 1960 to 1990, for example, the number of mainline Protestant churches on the northside rose from 39 to 45, while conservative Protestant churches there almost quadrupled from 22 to 82.� Note that these are not only churches catering to those pockets of northside poverty, as might be expected.� Rather, these are conservative churches appealing to the northside�s middle-class and upper-middle class populations � those very populations who comprise Marion County�s political and economic leadership.

4.� Religious perceptions.� Religious and secular trends are linked not only in the social and demographic make-up of the city, but also in other ways.� As middle-class whites left urban neighborhoods to newer suburban areas in the 1950s and 1960s, the language used to describe the city became suburban.� Suburban areas became the norm, while urban neighborhoods became �the inner city,� characterized their vulnerabilities, such as crime, poverty, and so forth.� Similar shifts in the religious realm were not far behind, reflected in the emergence of �urban ministry� programs.� Although intended to reinforce the responsibility of religious people for the entire metropolis, such language in fact reinforced the spatial and psychological segregation between city and suburb.� Now, ministry aimed at the �inner city� was labeled �urban ministry,� and was consciously separated out from other types of religious activities.

These four themes suggest that one cannot study the history of Indianapolis�s religion or that of any other city, without understanding the history of the city itself.� Denominational growth or decline, congregational mobility, or even the development of theological programs, all occurred in the context of demographic and social change.� Understanding these past changes not only helps to put the story of religion into a proper context, but also points people toward potential changes in the future.� That is, we will only be able to judge the future changes to Indianapolis�s religious and urban landscapes with a knowledge of how those landscapes looked in years past.

Walter Smith, Jr., �Report No. 26: Urban Church Commission,� Evangelical United Brethren Conference Proceedings, 1958.

Frederick Shippey, Protestantism in Indianapolis,1946 (Indianapolis: 1946), 55.

Clifford Green, ed., Churches, Cities, and Human Community: Urban Ministry in the United States, 1945-1985 (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdman�s, 1996).

Diane Winston, �Babylon on the Hudson; Jerusalem on the Charles: Religion and the American City,� Journal of Urban History 25, no. 1 (November 1998): 123.

Robert Fishman, �Megalopolis Unbound: America�s New City,� Wilson Quarterly 14, no. 1 (Winter 1990): 24-45.

�Religious adherents� are those who are identified as members of particular congregations or denominations, whether formally through declarations of faith, baptisms, or membership dues, or informally through familial ties.� The data discussed here relies on the United States federal census of religion conducted in 1926 and 1936 and the census of religion conducted by the Glenmary Research Center in Atlanta in 1970, 1980, and 1990.� Because these data were self-reported by denominations, and because denominations use different methods of counting adherents, one has to be careful when comparing groups.� For tracking a particular denomination over time, the data are more helpful.

�

Congregational data was derived from multiple sources, including Church Federation of Greater Indianapolis directories, annual denominational yearbooks, various city directories, and newspaper church listings.� The data in the chart are the totals for each congregational type and do not reflect whether individual congregations might have opened or closed from one decade to another.� (That is, if 20 new mainline Protestant churches opened, but 20 others closed, the overall mainline Protestant total would remain constant.)

�Mainline� refers to the seven Protestant denominations typically associated with America�s religious core: United Methodist, Presbyterian, Episcopalian, American Baptist, Disciples of Christ, Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, and United Church of Christ.� �Traditional Non-Mainline� denominations includes many historical Protestant denominations that are neither from this mainline core nor from the fundamentalist, Pentecostal, or evangelical denominations: African Methodist Episcopal, Unitarian-Universalist, Latter-day Saints, Christian Science, Friends, and several smaller groups.

ROUNDTABLE

On March 24, Research Notes hosted a roundtable discussion held at the Indianapolis Center for Congregations. Participants had been provided beforehand with the text of this issue of RN, and were invited to respond to the issues raised in the paper. Father Kenneth Taylor is pastor of Holy Trinity Catholic Church, and director of the office for Multicultural Ministry for the Archdiocese of Indianapolis. Andrea Neal is an editorial writer for the Indianapolis Star. James Davita is professor of history and chairman of the department at Marian College. John Hay, Jr. is director of the Central Indiana Regional Citizens League (CIRCL). Etan Diamond, a historian at the Polis Center, wrote the paper under discussion. Kevin Armstrong is pastor of Roberts Park United Methodist Church, and senior public teacher at The Polis Center. The following is an edited version of their discussion, which was moderated by Armstrong.

ARMSTRONG: Back in 1821, Alexander Ralston was commissioned to design this new capitol city in Indiana and the federal government gave him a four mile square area of dense forest. Ralston said, "The city will never grow that large," and so he designed the Mile Square, which today constitutes the center of downtown Indianapolis. Today we live in a metropolitan area that includes nine counties. Etan reminds us in his essay that terms such as neighborhood and city and community have come to be defined and redefined in very different ways as the urban-suburban context has changed. So how have you observed religious life in Indianapolis shaping or being shaped by that changing understanding of place and space?

TAYLOR: I think the clearest indication is in the movement of congregations. You see church buildings being turned over to other denominations or sold for other purposes and then the name of that congregation appears somewhere else � usually away from the center of the city, to the north or east or west. Those who operate separately from the territorial concept, which is used for Catholic parishes, have that particular freedom and when people move their church goes along with them.

DAVITA: In the last few years there have been some closings of Catholic inner-city parishes, a move that was pretty much unprecedented. Archbishops over the years have closed only four parishes within the city limits of Indianapolis. In two cases the financial situation was the consideration for closing; it wasn�t a case of people moving. There is only one Catholic parish that has moved, and that was partly due to movement of the population. St. Simon�s built a very nice new plant some miles north of its previous location. So we see a change in church buildings themselves brought on by the movement of population.

NEAL: I speak from the vantage of those who are left behind as the churches relocate to follow the population. Central Avenue United Methodist Church still exists at the corner of 12th and Central but the majority of its membership became the core of those who formed St. Luke�s United Methodist in the 1950s. St. Luke�s is now what Central Avenue used to be � the biggest Methodist church in the area. The Central Avenue congregation, in a much smaller form, has been struggling really ever since. In the last four years the church has been working with community groups in an effort to reframe itself. We still want to have a congregation in the building, but the building is going to become an urban life center serving community needs, rather than our trying to build up the congregation, which may not be possible because of the location.

TAYLOR: Historically, the Catholic Church was very territorial, and so you went to the church in whatever parish you lived in. In recent times that restriction has fallen away, and so you find Catholics who feel free to worship wherever they feel the most comfortable. At the same time, some Protestant churches are doing what we used to do, just opening up a new site. Eastern Star is opening up a second and a third site, and Light of the World, I think, has opened up a second site. Folks then don�t really see themselves as joining another church when they move.

ARMSTRONG: So there�s a development of franchises, in a sense, among congregations that once existed only in the retail community.

TAYLOR: Well, I see it as they�re starting their own diocese.

DIAMOND: In a previous time, Catholics were more territorial in their churchgoing and you�re saying that today they are less so. What has that done to their sense of territory? People used to think of the parish as the neighborhood. Has that gone out the window?

TAYLOR: I remember as a kid going to high school, I would just ask somebody, "What parish do you go to?" That would tell me where in town they lived � which of course doesn�t work anymore. When that territorial thing was tighter, the religious concerns of the people and the development and progress of the neighborhood were all one, and I think we�ve lost that. It�s harder, today. It�s harder to get a congregation that lives wherever to be as concerned about the neighborhood where the church sits.

ARMSTRONG: What does neighborhood ministry mean anymore, in light of that change?

TAYLOR: We still have parish boundaries that are set for us; we have a territory that we are responsible for, regardless of where the worshippers come from. So it�s up to us to keep that sense instilled in the congregation.

HAY: We�re attending a church right now called West Morris Street Free Methodist Church. And folks are attending that congregation from all over the place, from Zionsville and Brownsburg as well as from the immediate neighborhood. I think the growing edge of the church is from close in, from the immediate neighborhood, based on their outreach to children after school and on some of the support groups that are going on in the congregation. My goal as a member is to make sure that they don�t duplicate something good that�s already going on in the neighborhood. Let�s say there are things that the Mary Rigg Neighborhood Center is doing that we can complement, and things it isn�t doing that we need to pick up. For instance, middle school age youth � there is literally nothing in the immediate area going on for those kids.

NEAL: Three and a half years ago, Central Avenue Church was trying to make the decision whether to stay open or to close. And the neighborhood overwhelmingly was saying, "Your building, which is huge, with a gym and a theater and a massive sanctuary, is the linchpin of our neighborhood. And if it closes that pushes us closer to the precipice." At a fundamental level, neighborhood ministry can mean keeping open a really significant building. So that became our first mission.

DAVITA: One of The Polis Center�s first publications, I recall, said that there were no neighborhoods in Indianapolis. Indianapolis didn�t grow as many other large cities grew � by annexing independent towns, and the names of those towns became the names of the neighborhoods. So if we start from the premise that originally there were no neighborhoods in Indianapolis, then the congregation or the parish becomes the neighborhood. In fact, the word parish means neighborhood. The first members of those congregations whose origin is inner city lived within walking distance of the church. Catholics walked to church and Protestants, by and large, did too. Then as the streetcar came in, Protestants could live along the streetcar line and still get down to the church. And then the automobile came in. To place territorial boundaries around a church and say, well, we�re going to minister to that particular neighborhood, is to start essentially from point zero, given the historical development of Indianapolis.

HAY: There�s a part of me that feels like the whole idea of neighborhood or of being a neighbor is so devastated, is so far from our reality. I mean, we use the word neighborhood all the time and I love the word, but in our highly mobile state I think we�re still regathering and redefining it.

DIAMOND: Is it possible that when people in different parts of the metropolis use the term neighborhood, it just means something different to them? Someone on the Eastside might look at Pike township and say, "Oh, they�re not part of any neighborhood." But people in Pike township would say, "Yes we are."

NEAL: I grew up in the suburbs, in Fishers, and now I live in the city and they don�t feel anything alike. I didn�t live in a neighborhood as a child. I live in a neighborhood now. And maybe you can recreate neighborhood on a cul-de-sac, but I think you can�t. It�s not the same as when you can look into your neighbor�s house and you can walk your dog and see people you know. I don�t think we ought to try to force definitions where they don�t belong. Growing up on 126th Street, I hated that my mother had to drive me to school each day. I couldn�t walk anywhere. We had to drive to Noblesville to church.

TAYLOR: I think that even in the city the definition has changed, because at one point people lived in proximity while the kids all went to the same school. There were little markets all over the place. You saw each other at the market, the barber shop, the beauty shop. The church was just one entity among many where people crossed paths all the time. But now, even within the city, we have kids in different schools. We go shopping outside of the place where we live. There are many cases in my church where people see each other on Sunday, and won�t see each other again until next Sunday.

NEAL: So why do people move?

TAYLOR: The American dream, of course!

DAVITA: Dollars and cents drives you to better your house, to move away from the central city and business district.

HAY: A home is also the greatest investment that most people ever make. When I talk with neighbors, yes, they want a good neighborhood association, yes, they like what�s happening here. But they say, I have to get the best I can out of my house right now. I have to get to where the property value will rise to the next level. And I don�t know what folks are giving up, what they are missing in terms of neighborhood. I think there are things that do take the place of that old sense of neighborhood. I know from my own denomination, the whole focus on church growth was capitalizing on white flight, and on these new suburban communities in which people had no basic services for their families, so the ministry of the church was to become a community center. Even if you lived next door to somebody, you wouldn�t ordinarily see them or have anything in common with them unless you went to the same church.

NEAL: I think some suburban churches seem self-absorbed because they�re so busy at the task of recreating neighborhood for their members. That�s part of the reason there�s not enough urban ministry; they�re doing neighborhood ministry in their own congregations and it takes a lot of energy and resources to then go to another neighborhood and do it some more. At Central Avenue, we hope to get other churches to look at us as a mission site. All those suburban churches are sending mission funds overseas and we need money. Frankly, we need $5 million and that�s where the resources are, out there, and how can we make them see the urgency of that?

HAY: I was going to write you a check until you said $5 million...

ARMSTRONG: Let�s linger with this, because we�re really at the heart of the matter. We�re echoing some of the dichotomous language that�s used in a growing metropolis, in talking about suburban or neighborhood, inner city ministry or suburban self-absorption. There are some significant breaches in our language that reflect these divisions as the city grows. Tell me some more about how religious organizations and congregations have contributed to that breach.

HAY: I don�t know how much it has to do with theology as with practical considerations. Churches in suburban communities see themselves as being almost in a competition with other churches, other denominations, to church those who are moving out to new places. There is no sense of what is unique about that new community, or what they could contribute to it. A lot of the pastors do not even think in those terms. They have been trained and their leadership has supported them in thinking about "how can I grow my church?" and that�s where the pressure is placed.

TAYLOR: For urban ministry, it is a question of survival. The church is there to help people survive. The immigrants needed help to survive in a strange new culture. In the black churches, the church helped the membership survive in a hostile society. As people were able to move out to the suburbs the issues changed from survival to quality of life. You might say that the suburban churches find themselves with congregations who are more concerned with enhancing the spiritual quality of their lives. And it is hard when you have people whose issues are survival and people whose issues are quality of life trying to mix together.

ARMSTRONG: How have or how could religious institutions be mediating forces in uniting those divisions?

HAY: I think the church needs to think about the city and the region as a whole; to talk about a continuum of movement from survival issues to quality of life. That deterioration over here is related to growth over there. To understand that the city is much bigger and the region�s issues are much bigger and more in flux than we ever thought.

NEAL: I always like to quote Judy O�Bannon [wife of Governor Frank O�Bannon] saying that the last two things to leave a dying neighborhood are the church and the liquor store, and as long as the liquor store is there, you�d better figure out a way to keep the church open.

DIAMOND: It�s interesting that you�re talking about stability and survival, when at an earlier time churches were concerned with survival, with getting the immigrants into place, dealing with local pathologies, making things better. I think the whole concept of the inner city as a different place is only three or four decades old, and before that a place like Central Avenue Methodist was not at all conscious of being an inner city church, it was a church and it happened to be in a city. So is it overstating the case to say that things are so radically different than they used to be? Or is it just that what�s going on in the suburbs is what went on in these neighborhoods fifty years ago?

TAYLOR: I think that it is radically different, but it is being motivated by the same forces that have motivated people from the beginning of time. People have always wanted their future to be better than their past. And once upon a time that meant trying to move inside the walls of the city, because life was better inside the walls. The way cities have developed in America it�s been the other way around. The further out you could get the better your life would be. So the forces are the same, but I think the reality is different.

HAY: These struggling inner city congregations are really part of a great tradition. It�s rooted deeply in the prophecies of the Old Testament, and in the preference for the poor in the ministry of Christ. John Wesley worked among the poor and the uneducated. Phineas Brazee, who was one of the founders of the Church of the Nazarene, was committed to work with rescue missions and in places that were being bypassed and overlooked. Martin Luther King talked about the fact that when people refuse to help one another, everybody is impoverished. Whatever their economic circumstance, those who refuse to help or who distance themselves from those who are hurting are hurting themselves as well. And the opportunity for reconciliation and the opportunity for becoming human and whole comes by crossing those boundary lines.

NEAL: That reminds us also that a church is not a building, that a church is a community. But when we talked about saving Central Avenue I think we ran the risk of being associated with just wanting to save a historic building, and early on we went through a visioning process, to make sure that the building had a special role to play in creating community.

DIAMOND: When you talk about the people and the congregations moving out, what role did the denominations play?

DAVITA: Reactive. People moved out, and parishes were organized when there were sufficient numbers to support a new parish. So it�s not a question of the church encouraging move-outs but rather the church moving out because the people had moved. But then again what is church? We�re suggesting church is the people.

ARMSTRONG: So from your perspective, denominations were responding to the metropolitan change rather than influencing it. They were being reactive rather than proactive.

DAVITA: I think so. The immigrant groups by and large were the ones who demanded that church authorities establish parishes for them. The liturgy was in Latin and nobody understood it and therefore it didn�t make any difference. But for preaching, for ministry, and contact with the priest, not to know English was a handicap. And the end result was that ethnic churches usually separated from those that had an Irish-American congregation.

TAYLOR: That kind of reaction is still going on today. Archbishop Beuchlein [Archbishop Daniel M. Beuchlein, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Indianapolis] is getting a lot of pressure from various suburban areas � which says that people feel they have a right to go to church near where they live. When it comes to going to the store, going to school, you have to travel to go anywhere else in life, but when it comes to church, we deserve to have our own church in our own area.

DAVITA: There�s the other side though. How many Catholic churches in the inner city could survive without the automobile? What percentage of your congregation lives in the neighborhood?

TAYLOR: I don�t have the number, but it is higher than most people think. It could be around 50 percent.

NEAL: But there are exceptions to that too. The congregation of Tabernacle Presbyterian almost in its entirety moved north, but they decided that they would keep that building and they would stay rooted in that neighborhood and their neighborhood ministry, their recreation program, is exciting and growing every day. They�re just grabbing as many inner city kids as they can and embracing them.

ARMSTRONG: Well, let me ask you to summarize all this in this way. John represents an organization [CIRCL] that encourages citizens and groups to take an active role with metropolitan development. How do congregations and religious people matter in metropolitan development?

HAY: CIRCL is talking about civic engagement and about citizens becoming more a part of the decision-making process of central Indiana. If we bypass congregations, or don�t see their incredible civic involvement, I don�t think we can be effective.

NEAL: Working together is so much harder than working alone. It takes more time, it takes good communication, it takes teamwork. Churches in the inner city have hunkered down and hung in there so long on their own that to do it any other way is just incredibly difficult. If someone can mediate or facilitate these collaborative efforts, that�s great.

DAVITA: I think churches, like schools, are institutions of stability in neighborhoods, but I don�t think that government particularly appreciates either one. By not recognizing the contribution that these institutions make, government really diminishes its own purpose.

TAYLOR: People are motivated to make their lives better and in America that means moving out to the suburbs, and I don�t necessarily see that the church�s role is to try to change that. What I do see as part of our mission is to help people live their life to the fullest. It may mean helping people to survive so that they can move to the next step. It may mean working to change unjust situations such as trying to get laws changed. It may mean providing education for people. Whatever needs to be done, wherever we happen to be, to help create a situation where all people can freely live up to their God-given potential is a major role for the churches as I see them.

ARMSTRONG: Etan, any last words?

DIAMOND: There are interesting contradictions in things you all have said. There�s a sense that those in the inner city have some resentment of suburban churches for being who they are. Those people in suburbia are going to church in their neighborhoods. The inner city churches are also serving their neighborhoods, yet it seems that what goes on in suburbia doesn�t count, whereas what goes on in the inner city is more authentic. Unfortunately we don�t have somebody from one of these booming suburban churches who could defend themselves or say, actually we think of ourselves as a neighborhood church.

DAVITA: I think it�s because Christians have, down deep, an attraction to the poor, and therefore the real Christianity is in the inner city. We never pray for the rich. We pray for the poor.

HAY: I feel the contradictions within myself, and the tensions. In terms of congregational life the region is going in a lot of different directions that aren�t necessarily ready to be reconciled or directed toward some common goals. I don�t know that we�re anywhere near being able or ready to all join hands. Well, maybe we can do that! Maybe that would help us to bridge some of the other stuff.

ARMSTRONG: Well, thank you all for your participation. This is obviously but an opening chapter in what could be a long conversation.