The Martindale Brightwood neighborhood is bounded on the north by 30th Street; on the east by Sherman Drive; on the south by 21st Street until it meets Massachusetts Avenue and then south on Massachusetts to 10th Street; and on the west by the Conrail tracks.

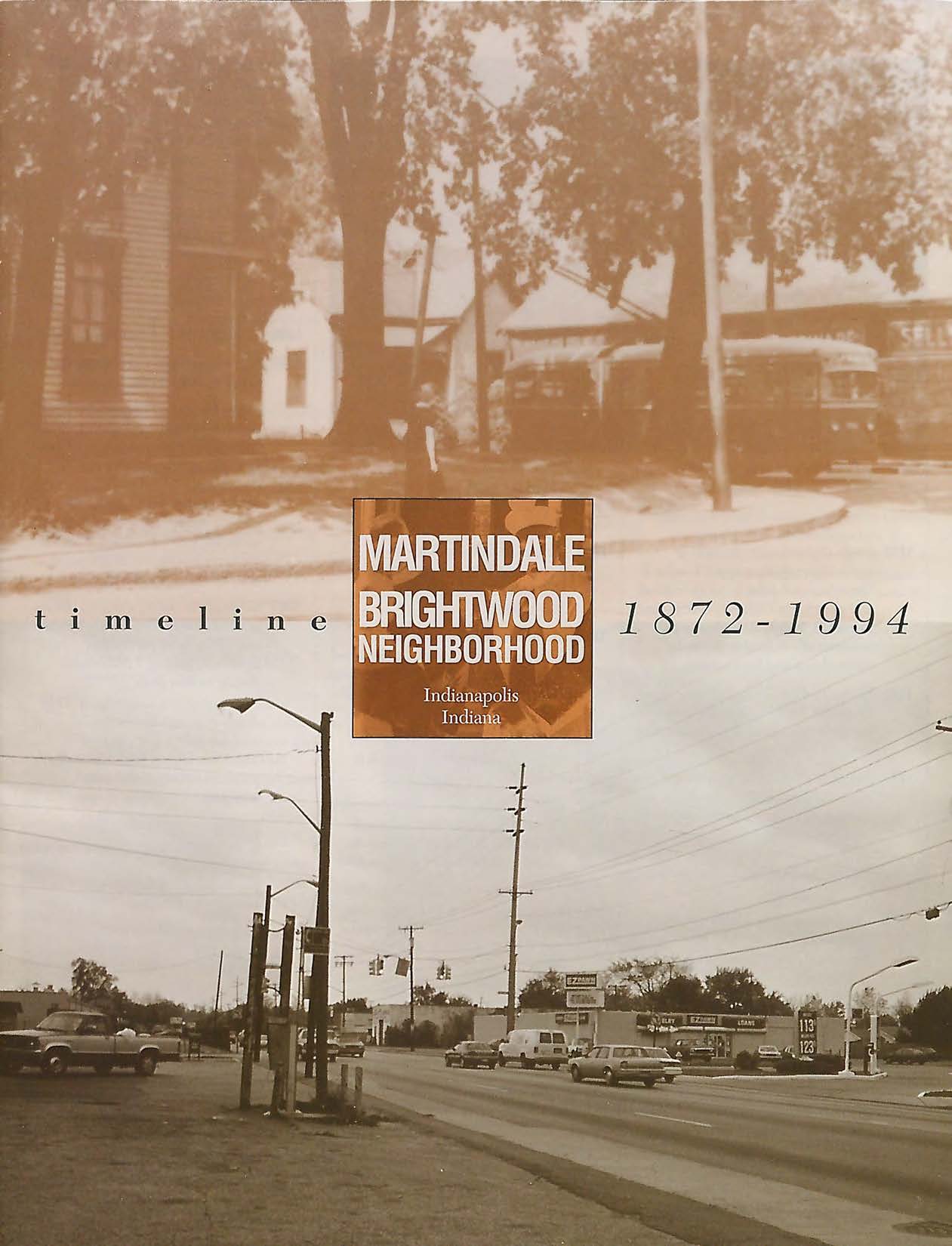

Martindale-Brightwood is a neighborhood situated on the near northeast side of Indianapolis bounded by 30th Street, Massachusetts Avenue, 21st Street, Sherman Drive, and the Northfolk Southern Railroad tracks. This area encompasses two previously independent settlements. Brightwood, the eastern section of the neighborhood, was first platted in 1872 and amended in 1874. Railroad workers on the “Bee Line” were the first to settle the Brightwood suburb which soon became the railroad center of Indianapolis. The town of Brightwood was incorporated in 1876 and remained autonomous until 1897 when it was annexed by Indianapolis. The Martindale area was settled in 1874, also by railroad workers who found employment in machine shops and manufacturing. Industrial growth in Martindale was supported by the nearby railroad lines and the area quickly became a working class suburb.

The blue collar population of Martindale-Brightwood before the turn of the century included a mix of African Americans and a growing proportion of foreign born or first generation European Americans. African Americans began to settle in residential areas around Beeler Street (later Martindale Avenue and still later Dr. Andrew J. Brown Avenue), the industrial center of Martindale at that time, and began building their own churches along the avenue. In contrast Brightwood continued to attract white residents who were skilled and unskilled workers; the 1880 census reports that about forty percent of the adult men were foreign-born or first-generation, predominantly of German, Irish, and British ancestry.

Brightwood developed as a small town before its annexation by Indianapolis. The town provided its residents with a high school located in the northeast part of Brightwood, private water works installed in 1894, and operated two volunteer fire departments: the “Wide-a-Wakes” and the “Alerts.” Station Street, located in the southeastern section of Brightwood became the town center. Station Street was developed as the business district and continued to be the commercial center of the neighborhood until the 1960s. In 1899 Brightwood was described as a “. . . thriving town of nearly 4,900 people. . . . it is a model city of cottages resembling a park. The fact that so many men living in the town work together in the great engine and car shops makes the community seem like one big family.” The same year extension of street-car service connected Brightwood with Indianapolis.

The beginning of the twentieth century continued to see Brightwood prosper as a result of thriving railroads and increased industrialization. Laycock Manufacturing Company, Topp Hygienic Milk and Ice Company, George F. Neher & Sons and the Big Four Railroads (Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis) were among the larger employers in the region. A Commercial Club was organized in 1911, for the purpose of building up the suburb and to obtain municipal improvements. The goals of the club were the establishment of a park and public playground and to build an addition on School #51 that would allow the teaching of high school classes. In addition to School #51, Brightwood also contained the parish school of St. Francis de Sales Catholic Church. The town had already received other public improvements such as a library in 1902, and it made plans for the improvement of the water works.

Martindale, in the west, continued to develop as an industrial and residential area centered around Martindale Avenue. The street was lined by a mixture of private homes, churches, and industry. Among the businesses operating in the Martindale area were the Indianapolis Gas Works, Wm. Eggles Field Lumberyard, Hoosier Sweat Collier Factory, the National Motor Vehicle Company, and the Monon Railroad yards. African American churches continued to be built in the area, and Martindale Avenue became the home to many African Americans. The African American population of Martindale was also provided with a school and Douglas Park was dedicated in 1921. Within a few years, by 1927, the park also operated a swimming pool. During the formative years of both Martindale and Brightwood the railroads continued to be the basis for the economy, however, following the relocation of the “Big Four” to Beech Grove in 1908 the industry slowly began to decline.

By 1944 most of the original railroad businesses had relocated and it was in this year that the railroad station in Brightwood was razed. The remaining railroad connections were moved by the New York Central (owner of the “Big Four”) to Avon, Indiana in 1960. The loss of the railroads proved to be detrimental to the economic status of Martindale-Brightwood in the post war years. With the loss of the railroad industry and the expansion of Indianapolis suburbs the neighborhood went through a period of transition. White residents began to relocate to the newly built suburbs. The migration away from Brightwood left behind a surplus of housing which was followed by an in-migration of lower income African Americans which continued throughout the next four decades. By 1960, African Americans accounted for approximately half of Brightwood’s population of 5,700. This amount would increase to over ninety percent of the population which had declined to 4,700 by 1990. Through this same period Martindale remained an African American center of small working class homes intermixed with industry. Manufacturing remained as a dominant industry and Ertel Manufacturing, current occupants of the old Atlas Machine Works grounds, is the areas largest employer with over 300 workers.

The 1960s also brought about plans for the construction of the I-65 and I-70 interstate which cut through portions of the Martindale-Brightwood area. The interstate which was begun in the sixties and finished in the seventies further displaced residents of the neighborhood. Although the infrastructure and economic development of Indianapolis would benefit as a result of this construction, the interstate represents an intrusion in the life of the neighborhood. Martindale-Brightwood was now divided by an east-west interstate and had lost a portion of its population. Residents moved, local businesses followed, and the old economic center of Brightwood, Station Street, began to be vacated. By the mid 1970s the street had lost a doctor’s office, accounting and bookkeeping services, a cafe, insurance company, Salvation Army store, pool hall, a pet store, and Cohen Bros. Department Store which had first opened its doors in 1897. By the mid 1980s the last remaining bank, a branch of Merchants, had announced plans to leave the community. The result of changes in economics and population changes in the 1960s were so drastic that by 1967 enough of Martindale’s near 6,000 families met the federal definition of “poor” to have Martindale declared a poverty target area. Through the seventies and eighties crime continued to increase and in the early nineties Martindale-Brightwood had been targeted by law enforcement for programs to combat gang and drug activity.

More changes followed. In 1971 Judge S. Hugh Dillin found the Indianapolis Public Schools guilty of segregation and ordered the desegregation of all single-race schools. This resulted in the institution of busing throughout Indianapolis and the decline of the neighborhood schools that had once been key to the identity of Martindale-Brightwood. Education in this neighborhood has a long history. In 1875 Brightwood began operating its own high school, known as school No. 12 of Center Township and was located at 27th and Sherman Drive. The school was short-lived, however, and had closed by the time that Brightwood was annexed to the city in the 1890s. Around the turn of the century the Washington School was operating in Brightwood and included manual training and special education.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, Indianapolis Public Schools and the parochial schools of St. Rita’s Catholic Church and St. Francis de Sales had been both educationally and socially important to the neighborhood. St. Francis de Sales school was the parish school serving Brightwood. The school was built in 1903 and remained open until 1970 at which time, as a result of declining church membership, it was forced to close. The school reopened in 1977, but was shut down permanently when the parish was closed in 1983. The property became the main campus for Martin University in 1987.

St. Rita’s was established in 1919 as the African American parish in Indianapolis and continued to flourish throughout the next few decades. Under the leadership of Father Bernard Strange, who came to the parish in 1935, the church and school became a vital part of the community. Father Strange proved himself to be a progressive leader of the church who began fighting for the desegregation of Catholic schools in the 1930s. He also directed much of his mission at St. Rita’s towards the congregation’s youth and school. St. Rita’s became known for a number of social activities open to the Martindale community and African Americans throughout the city. Father Strange developed sports leagues which included boxing tournaments and basketball. The school’s gymnasium was used throughout the fifties, sixties, and seventies to house weekly dances which, at their prime, attracted between 500 and 800 youths each week. Throughout this period the church and school continued to be actively involved in community programming.

Indianapolis Public Schools also have added to the Martindale-Brightwood identity. However, as a result of declining enrollments and busing, only schools 26, 37, and 56 remain open today. Brightwood has been served by IPS 37, 38, and 51. Prior to the federally mandated busing began in the seventies these schools remained very active within the communities from which their students came. Named in honor of its principle of thirty-three years, Hazle Hart Hendricks School 37 was Brightwood’s African American school. The school offered its students a variety of social activities including a jug band which played at downtown hotels, churches and hospitals during the thirties. In 1935 the PTA of school 37 was the first African American school to become a part of the State and National Congress of Parents and Teachers.

The John James Audubon School 38 became an active community center during the thirties and forties and worked to offer social and medical assistance throughout the neighborhood. As early as 1924 the school began operating a dental clinic for needy students of the community. During the Great Depression the school increased its social programming through the collection of donated clothing, serving of Thanksgiving Day meals, distribution of milk to the mal-nourished, and work with the Red Cross. This spirit of social responsibility continued through the war years when the school raised money through the sales of stamps and bonds to buy an ambulance. Contributions also continued to be given to the Red Cross, Community Fund, Children’s Museum, Christmas Seals, Riley Hospital Fund, Students Fund, and Merciful Relief. The school is now closed and the building at 2050 North Winter now houses the Full Gospel Deliverance Church.

Brightwood’s third elementary school was the James Russell Lowell School 51, which was known as the “mother school” of the other public schools in Brightwood. The school was situated in the southeastern part of Brightwood, at 2301 North Olney. The area surrounding School 51 was the most industrial section of Brightwood. The school has also been closed and its last use was as the home of the Church of the Living God, Pillar & Ground of Truth.

Martindale’s Francis W. Parker School 56 was known as “The Colored School.” The school served Martindale’s African American population and offered its students not only an education but social activities as well. Boys could join the “Cardinal Pioneer Club” which participated in field trips and community service and girls could join “The Girl Reserve Club” which was organized to “instill things of cultural value in the girls.” In the forties the school also offered medical examinations and immunizations.

Changes in the neighborhood and in IPS during the past twenty-five years have had definite effects upon the role of neighborhood schools. Declining enrollments, mandated busing, consolidation, and recent developments such as the select schools program have reduced the interaction between neighborhood and school. While the institutions remain located in the area, their significance as a neighborhood center continues to decline.

Community centers and churches have also been important to the development of a neighborhood identity in Martindale-Brightwood. The centers have quite often been operated by churches and have always represented a concern for the development of the neighborhood and its residents. In 1913, Hillside Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), under the pastorate of Rev. Charles M. Fillmore, opened a free medical clinic to serve the Hillside portion of Martindale-Brightwood. Many other community centers followed suit in the following decades.

In 1935 the Brightwood Community Center was founded. It headquarters were centrally located between Martindale and Brightwood at 2305 North Rural Street. The community center acted as a social and educational headquarters for many African Americans in the neighborhood. In 1940 Edna Martin became the director of the East Side Community Center which later opened as the East Side Baptist Center in 1945, at 1519 Martindale Avenue. The center has since relocated and was renamed in honor of Edna Martin after her death in 1974. St. Rita’s Catholic Church continued its community service through the institution of a summer youth center to combat juvenile delinquency in 1947, and a summer camp for underprivileged African American boys in 1949. St. Rita’s also involved itself with a neighborhood beautification project that same year. In the mid-sixties St. Rita’s begins offering a number of programs to aid underprivileged children and adults.

In the 1950s and 1960s a number of other churches also began community service projects. New Bethel Baptist Church began operating a community center which provided food, clothing, help for the unemployed, child care, and health services to the Martindale area. In 1962 the church began participating in “Operation Prove It,” an inner city interdenominational ministry program which involved seventeen North Side churches which shared the goals of improving inner city housing conditions, deterring juvenile delinquency, interracial tensions, and job insecurity. In 1957 Brightwood Methodist began offering Sunday school classes for learning impaired children. Hillside Christian Church relocated its congregation to the suburbs in 1961, but the building was purchased by the Association of the Christian Churches in Indiana for development of an “inner city” ministry.

In 1967, following the declaration that Martindale had been declared a poverty target area, the Martindale Area Citizens Service (MACS) organized to provide aid against the poverty, deteriorating houses, health problems, crime, and unemployment which threatened the neighborhood. Both St. Rita’s and Scott Methodist provided services for MACS. St. Paul AME Church followed suit in 1970 with the construction of its new community building which would be used as a community center for activities in District Three of the Model Cities program. Community centers have continued their involvement in Martindale-Brightwood to the present. In the eighties the NAACP, Brightwood Community Center, and several block clubs once again organized against unemployment, loss of business, crime, lack of housing rehabilitation funds, social services, red-lining, new houses, and commercial development. Today, neighborhood service centers include the Martindale-Brightwood Neighborhood Coalition, Brightwood Community Center, Edna Martin Center, St. Nicholas Youth Center, Oak Hill Civic Association, Oxford Terrace Association, Hillside Neighborhood Association. Gleaners Food Bank, a city wide relief agency, is also located in Martindale-Brightwood.

As illustrated in the development of community centers, religion has always played an important role in the neighborhood life of Martindale-Brightwood. When African Americans first began to move into Martindale in the late nineteenth century they brought with them a number of churches that still line Dr. Andrew J. Brown Avenue today. In spite of the survival of several congregations along this stretch of Martindale religious institutions have not always prospered nor remained in the neighborhood. The economy, racial changes, and urban development have all had an effect upon the religious nature of the community, especially since the fifties. As church members began to move out of the neighborhoods many churches relocated, leaving behind buildings which were either abandoned or adopted for use by a new congregation moving into the neighborhood. One result of over thirty years of transition can be seen in the concentration of churches presently located in Martindale-Brightwood. At present the neighborhood is home to over eighty churches which represent various Christian denominations. Several of them, such as St. Rita’s, St. John’s Baptist, St. Paul’s AME, New Bethel Baptist, Scott United Methodist Church, and Martindale Christian Church, have been active in the neighborhood for many decades. A great number more illustrate the transition of the neighborhood in the late twentieth century. Many were founded between the fifties and seventies. Store front churches have become a common sight throughout the neighborhood and now dominate the once thriving business district surrounding Station Street. Congregations such as Hillside Christian Church, Brightwood Methodist, and Brightwood Church of Christ, have relocated to the growing suburbs. And others such as St. Paul’s United Methodist Church and St. Francis de Sales Catholic Church dissolved in the eighties following many years of declining membership. The period of social and economic transition which had changed the demographics of Martindale-Brightwood had also had an impact upon the religious life of the neighborhood.

Martindale-Brightwood continues to be a neighborhood in transition. New housing developments have begun in recent years and community groups continue to work for an end to the other problems which have plagued their neighborhood. Yet much remains to be done to improve the neighborhood condition and to rebuild a community which has witnessed so much change in the past forty-years. The neighborhood will have to look for some of these answers in its past which offers a picture of people, organizations, churches, schools, and businesses working together to promote the well being of their neighborhood.