Printable Version

VOL 1, NO 2

May 1997

The Changing Face of Indianapolis Religion

by Etan Diamond and Arthur E. Farnsley II

We�ve all looked at photographs of a beautiful landscape, of some place frozen in time by the camera. As lovely as that picture might be, it is limited in one important respect: it does not tell us much about the past. Did that landscape always look so beautiful? How have nature or humans shaped it over time? Only by looking at old photos of the same site at different times can we begin to understand how a place has changed.

Like a photograph, a survey provides a snapshot of people�s attitudes or behaviors at a single point in time. It often reveals little about the past and how those attitudes have changed. Only by comparing different surveys from different points in time can we begin to see how attitudes have shifted, how the landscape has been altered.

We know from contemporary surveys of religious affiliation what the religious landscape of contemporary Indianapolis looks like. In the 1990s, Catholics are the single largest religious group, with Black Baptists and Methodists close behind. But how much does the modern lay of the land resemble Indianapolis of earlier decades, a city many of us still remember? How much has religion in our city changed?

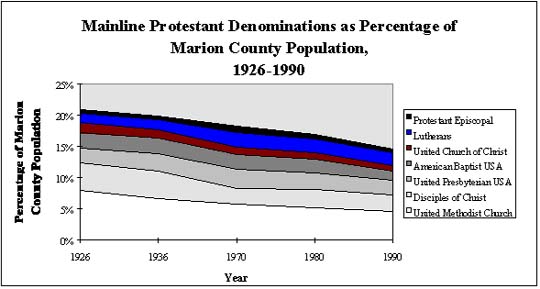

The experience of mainline Protestantism is instructive. In 1990, liberal Protestant groups, including Methodists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Disciples of Christ, white Baptists, Lutherans, and United Church of Christ members, accounted for only about 13 to 16 percent of all Marion County residents, depending on exactly which groups one counts as "mainline." This means that together these bodies make up between 25 and 30 percent of all members of religious organizations. Considering Indianapolis�s reputation as a mainline Protestant-dominated city, this figure seems low. How low, relative to the past, is confirmed by figure 1. These established Protestant groups have in fact experienced a steady decline since the 1920s, when they accounted for over 20 percent of the city�s population and nearly one-half of its church or synagogue membership.

Figure 1

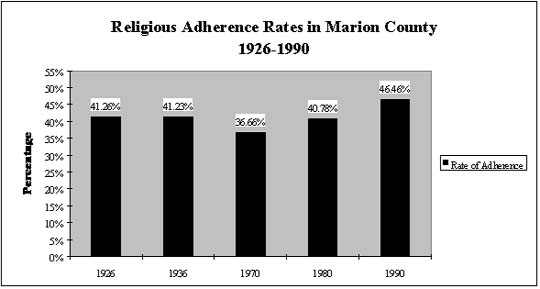

Was this decline simply part of a broader social movement away from religion in Indianapolis? After all, the "snapshot" of religion in 1990 suggests that Indianapolis has a particularly low adherence rate at 45 percent. But as figure 2 reveals, overall affiliation rates in Marion County have increased slightly since the 1920s. Mainline Protestant groups declined despite a counter trend toward higher membership in general.

Figure 2

The evidence of mainline Protestant decline in the midst of increasing rates of affiliation leads to a final question: if the population of the county was growing steadily (it doubled from 1926 to 1990), and membership rates of religious organizations other than mainline Protestants were growing (albeit slowly), then where do all of the new religious adherents come from?

One answer is that there was growth among Catholics. The present level of Catholic membership is actually more than double what it was in the 1920s and 1930s (Table 1). Catholics literally doubled in numbers between 1936 and 1970, from about 40,000 to somewhere near 80,000, far outpacing the rate of population growth in the county. Interestingly, Catholic membership numbers leveled off after 1970. From 1970 forward, their numbers are as stable--their line on the chart is as flat--as the numbers for mainline Protestants.

The segment labeled "All Other Groups" accounts for most of the growth in religious adherents in the 20th century. Most of the growth in religious membership during this century, and essentially all of the growth since 1970, has been among congregations that include both black and white independents, conservative denominations, and Pentecostals. Together, these groups have more than quadrupled over the past several decades. Although groups other than Christian are included in the "All Other Groups" category, there is no evidence that non-Christian religions have made substantial membership advances in this century. Evidence from cities such as Chicago and Detroit, however, suggests that Indianapolis might expect growth in these groups, especially Islam, early in the next century.

Table 1

Number of Adherents by Period

Denomination

1926

1936

Catholic United Methodist Church Disciples of Christ United Presbyterian Church in the USA American Baptist USA Lutherans United Church of Christ Protestant Episcopal Church All Other Religious Groups

As these various graphs and table suggest, Indianapolis�s contemporary religious landscape did not suddenly emerge in 1997. This complex landscape has been continually evolving, as religious groups have experienced different trajectories of growth and decline. We cannot tell the story of religion Indianapolis based solely on what we see around us today, because what we see has been shaped and conditioned by what came before. Indianapolis religion in the late 1990s looks the way it does because of shifts that have happened over the past several decades.Etan S. Diamond is a research associate at The Polis Center and Arthur E. Farnsley II directs the Faith and Community component of The Polis Center Project on Religion and Urban Culture.