American citizens expect a certain amount of personal privacy. In fact, “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures…” is protected by the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Over time, this protection has been extended nationally and at the state level to include personal information. For example, most of us are familiar with the notion of protection of an individual’s health information. This comes from the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Similarly, the Driver’s Privacy Act of 1994 ensures the privacy of information collected by state Departments of Motor Vehicles and the Fair Credit Reporting Act (amended by the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act) restricts use of information about the credit standing of individuals. Perhaps a more familiar consequence of the Fair Credit Reporting Act is the required truncation of credit card numbers on receipts – another way to keep personal information private.

But what about protections of our personal location? Who owns the information collected by cell phone companies about where we are and where we have been? Is it legal for law enforcement officials to use a global positioning system (GPS) technology to track suspects or prove whereabouts at a specific time? Although these questions are beginning to be answered in courts and as legislative outcomes, the answers are fractured, incomplete, and sometimes even conflicting from one state to another. These answers are of great interest to geographic information system (GIS) practitioners who may be called to create, analyze, distribute, or protect certain kinds of personal location information.

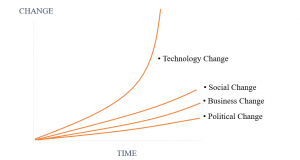

It should not surprise us that technology change is outpacing social, political, and legal change. Author Larry Downes noted in the Laws of Disruption that “Social, political, and economic systems change incrementally, but technology changes exponentially” (Downes, 1998).

GIS practitioners live in a technological world and are often the agents of technology change, especially related to location. The idea of all of us forging ahead without the guidance of social and legal norms reinforces the need for an ethics requirement within our practice (maybe another paper on another day) such as “A GIS Code of Ethics” created by the GIS Certification Institute (GISCI), which states:

“This Code of Ethics is intended to provide guidelines for GIS (geographic information system) professionals. It should help professionals make appropriate and ethical choices. It should provide a basis for evaluating their work from an ethical point of view. By heeding this code, GIS professionals will help to preserve and enhance public trust in the discipline.”

GIS practitioners should also make a deliberate effort to understand the current and proposed legal requirements regarding personal location privacy.

Personal Location Privacy and the Law

In an effort to help you be aware of the current legal environment, the list below references laws and court decisions that have the potential to affect our work and how we think about personal location data. This listing is not meant to be inclusive, especially since the legal landscape of personal location information is ever changing.

- United States v. Antoine Jones, 2012. In this decision, the US Supreme Court ruled that legal officials must obtain a warrant prior to attaching a GPS device to suspect’s vehicle.

- Carpenter v. United States, 2018. A search warrant must be obtained in order for law enforcement to obtain seven or more days of historic cellphone location data from a suspect’s phone.

- Riley v. California, 2014. A search warrant is required by police to search the contents of a suspect’s cell phone. Interestingly, location history was specifically used to illustrate the opinion.

- Closer to home, the Indiana Supreme Court ruled that police did not require a warrant to obtain historical cell-site location information if the information is held by a third party (telephone company) and the information is provided voluntarily. The US Supreme Court vacated that ruling in June 2017 by a 5-4 decision. S. Chief Justice John Roberts observed that Americans have a reasonable expectation of privacy of the location information that produces a “near perfect surveillance, as if [the government] had attached an ankle bracelet to the phone’s user.” This reasonable expectation supersedes the “third party doctrine.” The Indiana Supreme Court revisited the case in September of 2017, in part to hear oral arguments from the office of Indiana Attorney General that “notwithstanding the US Supreme Court ruling, police were exempt from the warrant requirement … due to the exigent circumstance of needing to halt an armed robbery spree (Carden, 2018).” This is an interesting argument that pits the reasonable expectation of personal location privacy against the importance of public safety and community well-being. The Indiana Supreme Court is expected to rule in early 2019.

- Personal location privacy includes information beyond cell phone records. In July of 2015, House Enrolled Act 1371 became IC 36-1-8.5. The language in this statute requires government units to dissociate the name of an individual if in a protected group as defined in this statute from the address of that person’s home if so requested. Of great interest here is that the emphasis of protection has moved from the data itself to how the data is distributed since this statute applies only to online search engines maintained by the government unit, not to searches performed “over the counter” at the government unit.

What’s next?

As noted on the GPS.gov web page about location privacy, “The use of GPS technology to covertly monitor suspects, employees, customers, and other people raises questions about individual privacy rights. Several lawsuits and legislative actions have sought to address these questions, but much remains unresolved today.”

The same holds true for personal location privacy in general. For example, as recently as January 10, 2019, this issue made national news when AT&T announced that the company would halt the practice of selling customer’s location data to third parties. However, this announcement came several days after US Congress began looking into misuse of the data. Just a few weeks prior to the AT&T news, we learned from the New York Times that many of the apps on our phones were collecting our personal location so that their developers could sell the data to advertising companies.

“To evaluate location-sharing practices, The Times tested 20 apps, most of which had been flagged by researchers and industry insiders as potentially sharing the data. Together, 17 of the apps sent exact latitude and longitude to about 70 businesses. Precise location data from one app, WeatherBug on iOS, was received by 40 companies. When contacted by The Times, some of the companies that received that data described it as ‘unsolicited’ or ‘inappropriate.’”

Conclusion

As our social, business, legal, and economic environments struggle to keep up with technology change, GIS practitioners can reasonably anticipate more legislation and more court rulings to determine appropriate methods for collecting, managing, and using personal location information. We should be watchful, as advisers, for these guidelines as they are being contemplated, and reflective about how new laws and court rulings will impact our customers and our GIS community.