Problem

The City of Indianapolis needed new strategies to address rising rates of crime and violence, which have spiked recently across the county and the U.S.

The City of Indianapolis needed new strategies to address rising rates of crime and violence, which have spiked recently across the county and the U.S.

SAVI developed a model and maps that allowed the City-County Council to target crime prevention funding equitably—in the neighborhoods that needed it most.

With crime rates rising across the U.S., a ground-breaking collaboration between SAVI and the Indianapolis City-County Council is bringing a fresh approach to the search for local solutions.

The core idea behind the Council District Crime Prevention Grants Program is that grassroots organizations can play a key role in reducing crime and violence in the city. That’s true for two reasons.

First, smaller organizations are accustomed to making efficient use of limited funds—so even small grants can make a big impact on their capacity. Second, they are well-dispersed throughout the city, which means they can reach populations that aren’t served by some of the larger organizations.

LeRoy Robinson, District 1 Councilor, conceived the basic idea for the program before COVID-19 forced many national organizations to temporarily close their doors. The pandemic created a window of opportunity to initiate and experiment with it.

“Traditionally, you had major organizations apply for funds throughout the city for crime prevention,” Robinson says. “But those centers were not located evenly throughout the city. You might have only four or five YMCAs and Boys and Girls Clubs.”

During the pandemic, at a time when the needs were spiking, many people who relied on those organizations were left without a vital source of support. “So, my thinking was, let’s do this a little bit differently,” Robinson says. “Let’s go down a level, below the traditional organizations. Because if I’m a non-traditional organization—based at a church, for example—I don’t have to follow the same guidelines as they do. I can stay open.”

SAVI model delivers greater impact

The program was innovative on a second level because it created five tiers of funding levels. Neighborhoods with the highest crime levels and risk factors were eligible for more funding.

And that’s where SAVI comes in.

Many people know intuitively where the rates of crime and violence are highest in the city. But gut instinct isn’t enough to justify a tiered funding structure. The City Council needed data.

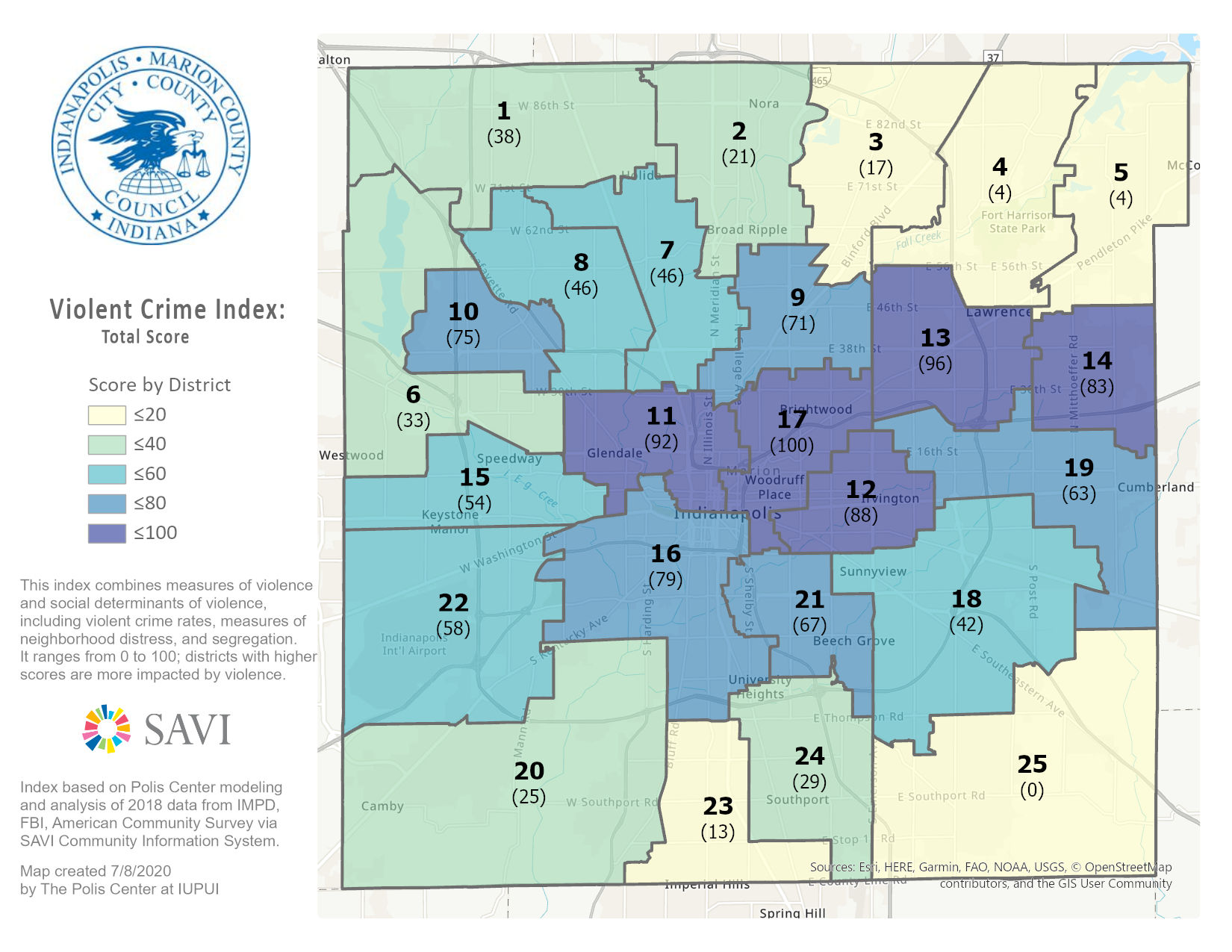

SAVI created an index that gave a score to each of the City-County Council’s 25 districts, from 0 (the lowest) to 100 (the highest), based on their violent crime rate and vulnerability to crime. For example, District 17—which includes the Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood northeast of the city’s downtown—scored 100 on the model’s violent crime index. In addition to a high violent crime rate, it also has the highest poverty rate, high unemployment, low vehicle access, and low education attainment. District 25—communities in the city’s southeast suburbs—scored 0, with low crime, poverty and unemployment.

Based on these scores, the program created five tiers of funding, with five districts in each tier. Tier 1 districts received $80,000 per district; Tier 2, $65,000; Tier 3, $50,000; Tier 4, $25,000; and Tier 5, $20,000.

Organizations of any size could apply for the grants, ranging in amount from $500 to $40,000. Programs funded in the first round of grants—which were awarded in June 2021—included $10,000 for an eight-week mentoring program at Zion Hope Baptist Church; $5,000 for a summer-job program for teenagers at New Direction Church; and $23,000 for a youth apprenticeship program at Freewheelin’ Community Bikes.

A second round of funding was distributed in December 2021. The Indianapolis Community Foundation manages the program.

Getting at root causes

Robinson believes the SAVI maps that were created to illustrate the data were “the most important component” in legitimizing and getting approval for the program.

“We knew anecdotally where the biggest needs were, based on high-crime and low-crime rates,” says Robinson, who hopes the program’s budget will double from the $1.25 million allocated in the initial pilot phase. “But we couldn’t sell that to taxpayers. The SAVI data—no one could refute it. When we allocated the dollars, no one could refute the data.”

Angela Plank, communications director of the City-County Council, agrees that the SAVI maps were key to moving the idea from the whiteboard stage to an on-the-ground reality.

“The visualization tells a story in an instant,” Plank says. “We don’t have the internal staff capacity to do the kind of analysis they did. We might be able to do some rudimentary form of that kind of analysis. But we would not be able to do it with the kind of depth and skill that SAVI brings to the table.”

This is the first time ever that the council made equitable funding decisions based on data to address disparities rather than equally distributing the funds. The council is now committed to district-specific crime prevention and policy informed by data. It is too soon to know what impact these grants have had on crime, although the Indianapolis Community Foundation has created metrics to track the results. If an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, as the adage goes, the results should more than justify the costs.

“The benefit of working with SAVI is that you’re looking at community-level indicators, and they show that what we’ve tried so far hasn’t worked,” Plank says. “We’re really looking at addressing the root causes of crime and violence instead of just policing our way out of it.”

For more information, contact Marc McAleavey.