The boundaries of the Fountain Square neighborhood are often debated, but one such description lists Washington Street on the north, State Avenue on the east, Pleasant Run on the South, and Madison Avenue on the west.

The history of Fountain Square is traditionally said to begin with Calvin Fletcher and Nicholas McCarthy’s purchase of the 264-acre farm of Dr. John H. Sanders in December 1835. Fletcher and McCarthy purchased the farm with the intent to “lay out this area southeast of the city center as ‘town lots’ and to sell the small parcels for a ‘handsome advance.’” [1]

The history of Fountain Square is traditionally said to begin with Calvin Fletcher and Nicholas McCarthy’s purchase of the 264-acre farm of Dr. John H. Sanders in December 1835. Fletcher and McCarthy purchased the farm with the intent to “lay out this area southeast of the city center as ‘town lots’ and to sell the small parcels for a ‘handsome advance.’” [1]

Included among those lots was what is now known as the Fountain Square neighborhood. Although the Fletcher family is credited with being the first settlers in the area, a band of Delaware Indians resided at the present site of the Abraham Lincoln School 18 (at 1001 East Palmer Street) as late as 1820.

With the notable exception of Virginia Avenue, settlement in the neighborhood was sparse until the 1870s. The earliest residents of the neighborhood were primarily a mixture of individuals from the East, the Upland South, and German and Irish immigrants.

In 1857 School No. 8 (named for Calvin Fletcher in 1906) was built at 520 Virginia Avenue, but it did not open until 1860 because of lack of funds to hire teachers. Reflecting a steady but slow population growth, a third story was added to School No. 8 in 1866.

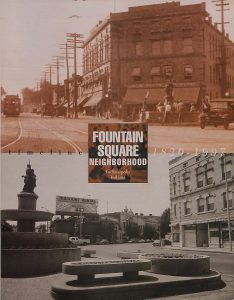

The Virginia Avenue corridor began to emerge as the South side’s commercial center in the 1860s. When the Citizen’s Street Railway Company laid tracks down Virginia Avenue and located a turnaround at the intersection of Virginia Avenue and Shelby and Prospect Streets in 1864, the neighborhood began to be known as “the End” by local residents. [2]

Reflecting the increasing Irish presence in the neighborhood, St. Patrick’s Catholic Church was built on Prospect Street in 1865. In 1870 St. Patrick’s Catholic Church was built a new building adjacent to the original structure, which then became a parish school.

Between 1870 and 1873 population growth along Virginia Avenue and Prospect Street was so rapid that the neighborhood had to be platted and re-platted eight times. One group in particular, the German immigrant population, enjoyed rapid growth in the 1870s. It was not until the 1890s, however, that Fountain Square developed the “distinctly German character” for which it later became known. [3]

Further enriching the neighborhood’s ethnic mix, small groups of Danish and Italian immigrants settled in Fountain Square during this same period. The construction of the first Edwin Ray (United) Methodist Church on Laurel Street in 1873, and the opening of Southern Driving Park (now Garfield Park) the next year, further expanded the neighborhood’s religious, social, and cultural environment.

In the 1880s the German-speaking congregation of the Immanuel Evangelical and Reformed Church (Immanuel United Church of Christ) purchased property on Prospect Street. This purchase and the opening of St. Paul’s Lutheran School (1889) on Weghorst indicate the growing German presence in Fountain Square. The neighborhood’s growing population in general was evidenced by a second public school on Fletcher Avenue (Henry W. Longfellow School 28), and the formation of High School No. 2. From 1886 to 1892 construction of the Virginia Avenue Viaduct was undertaken as a direct result of the construction of Union Station. Finally in 1889, the first of the neighborhood’s fountains was erected at the intersection of Virginia Avenue and Shelby and Prospect Streets. Variously known as the “Subscription Fountain” and the “Lady of the Fountain,” it gave the neighborhood its name. [4]

Between 1890 and 1900, Fountain Square became primarily identified as a German neighborhood. The number of German-owned businesses increased in the neighborhood’s commercial district, and the Southside Turnverein (now the Madison Avenue Athletic Club) opened on Prospect Street in 1900. This decade also saw the construction of a number of new schools. School No. 31 (Lillian M. Reiffel) on Lincoln Street opened in 1890, while School No. 39 (William McKinley) opened on State Street in 1895. High School No. 2 merged into Emmerich Manual Training High School in 1895, and the building at 520 Virginia Avenue was turned into a junior high school. In 1896 the city’s third branch library opened in the neighborhood at Woodlawn and Linden Streets.

A similar pattern of growth and expansion characterized the neighborhood’s churches in these years. In 1891 Second English Evangelical Lutheran Church was founded and began meeting on Virginia Avenue. In 1893 this church moved to a new building on Hosbrook Street, and in 1910 it changed its name to St. Mark’s (English) Evangelical Lutheran Church. In 1921 St. Mark’s moved to its present location on Prospect Street and sold the Hosbrook Street property to the Salvation Army. Immanuel Evangelical and Reformed Church dedicated its new building on Prospect Street in 1894, and in 1899 Emmanuel Baptist Church was founded.

The first three decades of the twentieth century were a period of continued commercial and cultural growth for Fountain Square. In the early 1900s Fountain Square’s May Day Celebration, including a parade and dance in Garfield Park, became known as the city’s “big event in the days before World War I.” [5]

The building of a pagoda in Garfield Park (1903) to house musical performances inaugurated a two-decade-long building program that transformed Fountain Square into the city’s first theater district. Between 1909 and 1929 eleven theaters were built in the neighborhood. Included among those theaters were: the first Fountain Square Theater (1909), the Airdome (1910), the Bair (1915), the Iris (1913), the Sanders Apex (1914), the Granada (1928), and the second Fountain Square Theater (1928).

Fountain Square also enjoyed continued growth as the Southside’s primary commercial district. The opening of the Fountain Square State Bank (1909), the Fountain Square Post Office (1927), Havercamp and Dirk’s Grocery (1905), Koehring & Son Warehouse (1900), the Fountain Square branch of the Standard Grocery Company (1927), the Frank E. Reeser Company (1904), Wiese-Wenzel Pharmacy (1905), the Sommer-Roempke Bakery (1909), the Fountain Square Hardware Company (1912), Horuff & Son Shoe Store (1911), Jessie Hartman Milliners (1908), the William H. and Fiora Young Redman Wallpaper and Interior Design business (1923), the Charles F. Iske Furniture Store (1910), The Fountain Block Commercial Building (1902), and the G.C. Murphy Company (1929), are a few examples of this phenomenon.

Fountain Square’s growing population was reflected as well in the opening of School No. 18 (Abraham Lincoln) on East Palmer Street in 1901, followed by the construction of additions in 1906 and 1915. Building programs were also carried out at School No. 8 in 1915 and at School No. 31 in 1918. The launching of extracurricular classes in nutrition for both parents and students by School No. 28 in 1924 suggests the partnership between local residents and Fountain Square’s educational institutions.

The neighborhood’s religious, ethnic, and racial composition became more complex during the early years of the century. In the early 1900s the African-American members of Olivet Baptist Church moved their meeting place from Beech Grove to a location at Prospect and Leonard Streets. In 1927 Olivet moved to its present location on Hosbrook Street (former home of St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church). Toward the latter part of this period, newcomers from the southern mountains of Appalachia began moving into Fountain Square. In addition, St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church organized Emmaus (German) Lutheran Church on Prospect Street (1904) in order to minister to the expanding German population in the neighborhood.

Reflecting this same growing diversity, these years also witnessed the building of additional “mainline” churches such as the Morris Street (United) Methodist Church (1905), the Emmanuel Baptist Church (c. 1916), the Victory Memorial (United) Methodist Church (1919), and the Calvary (United) Methodist Church (1926). Newer denominations—for example, the Laurel Street (Assemblies of God) Tabernacle (1913), and a Church of Latter Day Saints’ Chapel (1927)—also moved in the area.

In 1919 the “Subscription Fountain” was accidentally toppled when a local merchant “strung a rope supporting a large banner advertising a sale from his store and attached the other end of the banner to the statue. A wind blew up, and the weight of the banner caused the statue to topple to the ground.” [6]

In 1922 Mayor Samuel “Lew” Shank decided that Fountain Square should be the recipient of a bequest for a fountain in honor of former Congressman Ralph Hill specified in the will of his widow, Mrs. Phoebe J. Hill. The new fountain, topped by Myra Reynolds Richard’s sculpture the “Pioneer Family,” was unveiled in 1924. In 1927 another notable disaster occurred when St. Patrick’s Catholic Church burned in a fire set by an arsonist. The “crash of the burning steeple was one of the spectacles of the decade,” the Indianapolis Times reported. [7]

The present church of St. Patrick’s was built at the same location in 1929.

Between 1930 and 1960 Fountain Square experienced a number of profound changes still felt in the neighborhood. Prior to the 1950s it had come to be viewed as a solid working class neighborhood with a markedly German character. As a result, all of the inherent assumptions (many of a positive nature) about German immigrants came to be attached to the neighborhood itself. After the Second World War, however, increasing numbers of residents from Appalachia moved into the neighborhood. Citizens of other neighborhoods often attached negative stereotypes to Appalachian immigrants and extrapolated these perceptions to the neighborhood. It remained overwhelmingly white in composition, although the number of African-Americans living in the area grew slightly—from three to four percent of the population—during this period.

The 1950’s witnessed the beginning of the economic decline as new developments further south eclipsed Fountain Square’s long-standing role as the Southside’s primary commercial center. The closing of all of the neighborhood’s theaters provided an obvious example of Fountain Square’s commercial decline. A symbolic example was the removal of Fountain Square’s fountain to Garfield Park in 1954.

While the neighborhood’s commercial interests steadily declined, the schools and churches of Fountain Square remained active. In 1934 School No. 18’s paper, the Lincoln Log, received national recognition, as did School No. 39’s news magazine, the Broadcaster, in 1939. Periodic health examinations for children in the first, fourth, and eighth grades were begun at School No. 28 in 1939. In 1946 the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), working in partnership with the Federation of Churches, instituted a Week-Day-Religion Program at School No. 39. Gymnasiums were added to School No. 8 in 1942 and to School No. 18 in 1949. During these same years junior chapters of the Red Cross were formed at schools No. 18 and No. 28.

In 1950 the Fountain Square Church of Christ, organized by the Irvington Church of Christ, moved into quarters at Spruce and Prospect Streets. That same year, the Laurel Street Tabernacle built a new building on Laurel Street. In 1954 Rev. James W. “Jim” Jones, a former associate pastor at the Laurel Street Tabernacle, established his first independent congregation, the Community Unity Church, at Hoyt and Randolph Streets. In 1956 Jones relocated to North New Jersey Street where he organized the first People’s Temple.

In the 1960s and 1970s construction of the “Inner-Loop” of Interstate 65/70 displaced 17,000 of the city’s residents. Among the hardest-hit neighborhoods in Indianapolis was Fountain Square, which lost over 6,000 residents during the 1960s (this number represented almost 25 percent of the total population of the area) and most of its housing stock built between 1870 and 1910. [8]

The interstate also created a “physical barrier” between Fountain Square’s commercial district and “adjacent residential districts” (such as Fletcher Place). [9]

In the spring of 1969 Mayor Richard G. Lugar held a conference on Appalachia that was attended by representatives of local church organizations, social service agencies, the Indianapolis Public Schools, and a number of government agencies. As a direct result of this conference, the Community Service Council of Metropolitan Indianapolis released a report on The Appalachian in Indianapolis in 1970. For purposes of the report, the term Appalachian was defined as being “any rural, poverty-stricken, white individual who has migrated to Indianapolis from that area of the country designated Appalachia by the Appalachian Regional Commission.” [10]

Designated by the report as one of several “pockets of Appalachians” in the city, Fountain Square’s population was deemed to be “mixed” in terms of time removed from Appalachia. In addition, the report concluded that most of the neighborhood’s Appalachian residents had come from and were continuing to come from Kentucky and Tennessee.

Despite this close identification of Fountain Square as an Appalachian “pocket,” the report nonetheless concluded that the city’s Appalachian residents—including those in Fountain Square—did not display enough “uniquely Appalachian” characteristics to warrant a continuation of the study. In fact, the report concluded “local concerns and efforts might more productively be turned to seeking solutions to the problems of the poor in general.” [11]

From 1970 to the present Fountain Square increasingly has become the focus of local attempts to revitalize the surrounding neighborhood. Symbolic of the beginning of this new phase in the neighborhood’s history was the return of Fountain Square’s fountain in 1969. This process of revitalization has been marked by the formation of a number of community-based organizations. In 1978 a number of these organizations—including the United Southside Community Organization (USCO), the Southeast Multi-Service Center, and the Fountain Square Merchants Association—pooled their resources to form the Fountain Square Consortium of Agencies. That same year Fountain Square became a “treatment area” for Community Development Block Grant funds. In 1979 the Fountain Square-Fletcher Place Investment Corporation (FSFPIC) was formed with Community Development Block Grant funds. Its stated purpose was to renovate homes for low-income families and the elderly.

Between 1980 and 1982, more than $3 million was invested in Fountain Square, and in 1983 the commercial district was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. In addition, the Metropolitan Development Commission designated the near Southeast side, including Fountain Square, as an Urban Renewal Area in 1983. By the late 1980s a number of new businesses, such as the Downtown Antique Mall and the J.W. Flynn Insurance Company, had relocated to Fountain Square.

Since the 1970s Fountain Square’s schools and churches have experienced significant change. By 1973 School No. 28 had moved to Laurel Street, and in 1980 School No. 8 was closed. In 1987 School No. 39 was engaged in the district’s Effective Schools Program as well as the Partner-in-Education program, the Big Brother Big Sister program, and Butler University’s Project Leadership Service program. In 1989 School No. 39 moved into a new building on Spann Avenue.

In 1972 the Pentecostal Church of Promise was founded on English Avenue, and in 1986 the Life Unlimited Christian Church opened on Randolph Street. Today, the neighborhood is home to over thirty such “store-front” churches. By the late 1980s the food pantry at Emmaus Lutheran Church had expanded its operations to cover the entire area within the 46203 ZIP-code. In 1991 members of Edwin Ray United Methodist Church formed the Fountain Square Church and Community Project. Its stated mission was to “revive community fellowship and reclaim the neighborhood for resident home owners.” [12]

But two years later, Edwin Ray United Methodist Church closed as a result of an aging and shrinking membership and spiraling repair costs. The Church and Community Project was salvaged, however, when it merged with the Fountain Square-Fletcher Place Investment Corporation to form the South East Neighborhood Development, Inc. (SEND).

Although Fountain Square remains an “area of special need,” according to the Department of Metropolitan Development Planning Division (DMD), the neighborhood also is rich in commercial and cultural activity. [13]

Home to more than forty churches and served by a variety of community service organizations and a number of local institutions willing and able to take an active role in the neighborhood, Fountain Square appears to have the resources it will require to face the challenges of the future.

Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission, Historic Area Preservation Plan: Fountain Square (Indianapolis: 1984): H-2.

“Points of Interest: Fountain Square,” Indianapolis Star, 19 May 1985, B-12.

“Commerce In Area Dates Back Over 100 Years,” The Spotlight, 29 August 1984.

“Fountain Has Storied History,” The Spotlight, 29 August 1984.

James Rourke, “Residents Say It Will Flower Again,” the Indianapolis Times, 10 December 1961.

Rourke, “Residents Say It Will Flower Again.”

Historic Area Preservation Plan, AN-9.

Marilynn Bickley, Research Assistant, The Appalachian in Indianapolis(Indianapolis: Community Service Council of Metropolitan Indianapolis, 1970): 2.

Ibid., 26.

Susan Besze, “Patience Pays Off For Fountain Square,” Indianapolis Star, 28 July 1991.

Department of Metropolitan Development Planning Division, “The Southeastern Neighborhood,” (Indianapolis: DMD, 1994).